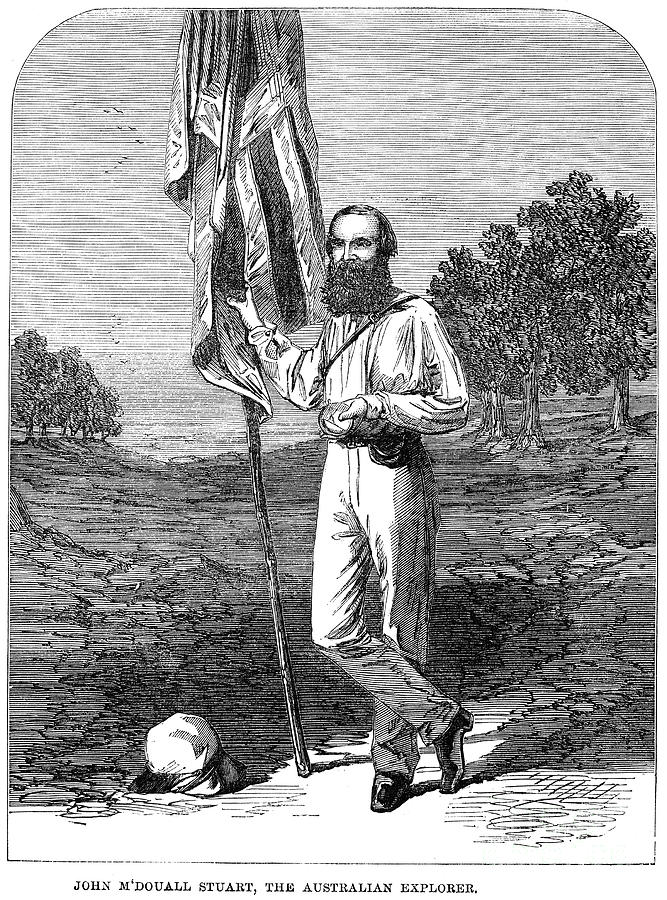

John Mcdouall Stuart

John McDouall Stuart Today I find from my observations of the sun, that I am now camped in the Centre of Australia. Stuart's Memorial Adelaide John McDouall Stuart, one of the most important people associated with South Australian exploration, was born in Dysart, Fifeshire, Scotland, on 7 September 1815.

Educated at Edinburgh and attended the Scottish Naval and Military Academy and later graduated as a civil engineer. He arrived in South Australia in January 1839 and soon found work as a surveyor. Within a short time he bought is own instruments and horses and started out in business for himself. In 1843 he became a farmer but already was an excellent bushman and restless adventurer. After a year of farming he was glad to join 1844 expedition. During this expedition they were stuck in the desert for six months. James Poole died and Stuart became second in command, drawing most of the maps as Sturt was almost blind.

It was to be eighteen months later before they reached Adelaide again. Later Stuart made several other expeditions before penetrating the desert areas beyond the salt lakes north of Port Augusta. During the 1850s there was a constant push for more discoveries to counteract the gold discoveries in Victoria which were draining South Australia of its male population.

Not only did they search the for and, they were also looking for farming and grazing land and for several years the South Australian government kept men in the field for that purpose. During these years Stuart was in the Northern Flinders Ranges surveying, prospecting and exploring, financed mainly by the brothers and his friend William Finke. In May 1858 Stuart set out, with one assistant, Mr Forster, and an Aborigine, on one of the most remarkable journeys in the whole of Australian exploration.

They travelled four months, covered more than 2000 kilometres, discovered huge tracks of good grazing land and had survived on rations which were suppose to have lasted for only six weeks before arriving at Streaky Bay. His last diary entry for that trip read, Saturday, 11 September. Arrived at Mr Thompson's station, Mount Arden. I cannot conclude this narrative without acknowledging that it was with the advice and assistance of my friend Mr Finke solely, that I undertook this exploration of the country. He continued, I therefore look upon him as the original pioneer of all my subsequent expeditions, in which our friend Mr Chambers afterwards joined. Stuart gave his maps and diary to the government and in return received.nothing. The Royal Geographical Society of London rewarded him with a gold watch.

In April 1859 he went north again and it was on this trip that his assistant David found artesian springs on 12 April and had them named after him. Many other springs were discovered on that trip which eventually led them to The Neale. Stuart's third expedition started on 4 November 1859 from Chambers Creek. His fourth expedition also started from Chambers Creek where they left on 2 March 1860, this time to find the centre of the continent. On 4 April the party crossed a very large creek 'with the finest gum trees we have yet seen. I have named it the Finke after William Finke.

On 22 April 1860 he had reached the centre of Australia and wrote in his journal, that he would plant the British flag tomorrow, 23 April, at what he had named Mount Sturt. On 25 April 1860 he wrote 'There is a remarkable hill about two miles to the west, having another small hill at the north end in the shape of a bottle; this I named Mount Esther at the request of the maker of the flag'.

Knowles was working at Moolooloo when Stuart arrived for his trip to find the Centre of Australia. When Stuart realised that he had not taken a flag with him it was Esther who made one for him. Refusing any money she was happy to have a suitable place named after her by Stuart. Stuart's greatest achievement was the south-north crossing of the continent and back in 1861-62. The party, which included, among others, 19 year old John William and Stephen King, left Adelaide on 26 October 1861 and reached the Indian Ocean on 24 July 1862. The next day the Union Jack, embroidered by Elizabeth Chambers with Stuart's name, was nailed on a tree, followed by three cheers for the Queen.

On his return, who had been again second in command, wrote to his brother from Mount Margaret Station on 30 November 1862, You will, I am sure, be very much pleased and gratified to hear of the safe arrival here of all our party and the unbounded success that has attended Mr Stuart's third attempt to reach the coast'. He went on to say that they had been away from Mount Margaret for forty-four weeks, but would remain at the station for some days to give the horses some time to recover before moving further south. Being well aware of the hopes and desires to have an overland telegraph connection with England, Stuart wrote in one of his reports that there would be a few difficulties in the way, but none which could not be overcome and make to repay the cost of such an undertaking. As a result of this journey, the opening up of the Northern Territory was made possible, and a route discovered for an linking South Australia with England and the rest of the world in 1872. In 1863 Britain added the whole of the to South Australia, a decision greeted with great enthusiasm by most South Australians. George Fife though believed the new area to be too big a responsibility for South Australia.

Because of the severe hardships he suffered on his expeditions, Stuart was in poor health and tried to settle down at Moolooloo. He returned to Scotland on 25 April 1864, the same day the Henry Ellis left for the Northern Territory with surveyors, settlers and officials. He lived with his sister and later moved to London with her where he died on 5 June 1866 at the age of fifty.

His funeral was attended by only 7 people. They included 4 relatives, 2 members of the Royal Geographical Society and Alexander who happened to be in London at that time and read his death notice in the Times. The name Alexandra Land which Stuart would have liked for the Northern Territory was never used. The transcontinental still bears his name.

Stuart Terrace, Stuarts Well, Stuart Town, Stuart Park, the schooner John McDouall Stuart, Stuart Caravan Park and Central Mount Stuart are all named after John McDouall Stuart. On his arrival back in Adelaide in 1862, Caroline Carleton, author of the, wrote, Full many a weary league Of hunger, thirst, and pain Our brave explorer trod, And traversed o'er again, Before he reached the goal, And cooled his burning brow, And stayed his halting steps Where the northern waters flow. Grim silence reigned supreme, Save alligator's plash, Or sea-mew's shrilly scream, Or ocean's restless dash; Yet flashed that leader's eye, And triumph filled his soul As he heard the bird's discordant cry, And saw the waters roll. Ten years later, to mark the tenth anniversary of Stuart's historic trip, Carleton added another two verses.

Methinks t'were worth a life To stand as there he stood- Forerunner of a dauntless race, Proud rulers of the flood. Across the desert waste He hears their hurrying feet; He sees the flashing wires That mighty empires greet. His dream is all fulfilled, Responsive echoes ring Around the circling earth, Sped on the lightning's wing. And what hath he? - a distant grave; Unblazoned is his name; And what have we?

- a beaten path To honour, wealth, and fame. Stuart is buried in the Kensal Green Cemetery, London.

Pictures supplied by Glenn Trussell 'because of the close and friendly association between Stuart and my great grandfather James Trussell of Cobdogla Station'. For information about the. If you would like to find out more, please go to HOME PAGE for more information. Thank you for visiting Flinders Ranges Research, We hope you enjoy your stay and find the information useful. This site has been designed and is maintained by FRR.

London, England Occupation Explorer of Australia, surveyor, grazier John McDouall Stuart (7 September 1815 – 5 June 1866), often referred to as simply 'McDouall Stuart', was a Scottish explorer and one of the most accomplished of all Australia's inland explorers. Stuart led the first successful expedition to traverse the Australian mainland from south to north and return, through the centre of the continent. His experience and the care he showed for his team ensured he never lost a man, despite the harshness of the country he encountered. The explorations of Stuart eventually resulted in the 1863 annexation of a huge area of country to the Government of South Australia.

This area became known as the Northern Territory. In 1911 the Commonwealth of Australia assumed responsibility for that area. In 1871–72 the was constructed along Stuart's route. The principal road from to was also established essentially on his route and is now known as the in his honour. The South Australian Surveyor-General, Stuart's superior officer, was the famous explorer Captain, who had already solved the mystery of the inland-flowing rivers of, in the process discovering the, travelling the full length of the, and tracing the to the sea. Stuart remained with the Survey Department until 1842 and then worked in the as a private surveyor and grazier.

In 1844 Captain Sturt embarked on an expedition into the arid interior, and engaged Stuart as a draughtsman. Sturt's expedition penetrated further north than any previous attempt, at the cost of great hardship. Instead of the hoped-for inland sea, the explorers found two of the most fearsome arid areas anywhere in Australia: and the. After second-in-command James Poole died of, Sturt appointed Stuart in his place. Both men survived to return to Adelaide, but suffered greatly from scurvy. Sturt never really recovered and soon returned to England; the younger Stuart was unable to work or travel for a year. Stuart returned to his trade as a private surveyor, spending more and more time in remote areas, and moving to for several years before moving again to the northern where he worked for the wealthy pastoralists, and, exploring, prospecting for minerals, and surveying pastoral leases.

It is alleged that he was a member of 's expedition of May and June 1857 looking for grazing country north and west of and a private expedition to with (later to become editor of ) in 1858. First expedition On 14 May 1858, with financial backing from William Finke, Stuart set off on the first of his six major expeditions. His aim was to find minerals, a land which the Aborigines called Wingillpinin, and new grazing land in the north-west of South Australia. Stuart set out from ' station Oratunga, taking as companions two of Chambers' employees (a white man named Forster and a young Aboriginal man), half a dozen horses, and rations for six weeks, all provided by Chambers, a pocket compass and a watch. From the Flinders Ranges, Stuart travelled west, passing to the south of, then north along the western edge of Lake Torrens.

He found an isolated chain of semi-permanent waterholes which he named Chambers' Creek (now called Stuart Creek). It later became crucially important as a staging post for expeditions to the arid centre of the continent. Continuing to the north-west, Stuart reached the vicinity of (not realising that there was a fantastically rich field underfoot) before shortage of provisions and lack of feed for the horses forced him to turn towards the sea 500 kilometres to the south. A difficult journey along the edge of the brought Stuart to Miller's Water (near present-day ) and from there back to civilisation after four months and 2,400 kilometres. This expedition made Stuart's reputation and brought him the award of a gold watch from the. Second expedition.

Soon after his return from his first expedition, Stuart applied for a pastoral lease at Chambers Creek. As the discoverer he was already entitled to a lease, but wanted rights to a larger area. As a bargaining chip in the negotiation process, Stuart offered to do the surveying himself and in April 1859 he set off with a party of three men and 15 horses. This gained for him the firm support and confidence of the, himself a keen explorer.

The Chambers Creek survey complete, Stuart explored to the north again, aiming to reach the border between South Australia and what is now the (at that time still a part of ). Although still well supplied with rations and not short of water, the expedition turned back about 100 kilometres short of the border because they had no more horse shoes (an essential item in that arid, stony region). Importantly, however, Stuart had found another reliable water supply for future attempts: a 'beautiful spring' fed by the then-unknown. He wrote: I have named this 'The Spring of Hope'. It is a little brackish, not from salt, but soda, and runs a good stream of water. I have lived upon far worse water than this: to me it is of the utmost importance, and keeps my retreat open.

I can go from here to Adelaide any time of the year and in any sort of season. He returned in July with reports of 'wonderful country'—an extraordinary description of territory that is now barely able to support a few cattle. Third expedition At around this time in Australia, exploration fever was reaching a peak. Several factors contributed. At 'home' (as Australians still called Britain), public attention was focussed on the search for the source of the, with the competing expeditions of, and all contending for the honour of discovery. Like the interior of Africa, inland Australia remained an embarrassing blank area on the map and although the long-held dreams of a fertile inland sea had faded, there was an intense desire to see the continent crossed. This was the apex of the age of heroic exploration.

Additionally, there was the factor of the. Invented only a few decades earlier, the technology had matured rapidly and a global network of undersea and overland cables was taking shape. The line from England had already reached India and plans were being made to extend it to the major population centres of Australia in and New South Wales. Several of the mainland colonies were competing to host the Australian terminus of the telegraph: Western Australia and New South Wales proposed long undersea cables; South Australia proposed employing the shortest possible undersea cable and bringing the telegraph ashore in Australia's.

From there it would run overland for 3,000 kilometres south to Adelaide. The difficulty was obvious: the proposed route was not only remote and (so far as European settlers were concerned) uninhabited, it was simply a vast blank space on the map. At much the same time, the wealthy rival colony Victoria was preparing the biggest and most lavishly equipped expedition in Australia's history; the Victorian Exploring Expedition, to be led by Robert O'Hara Burke. The South Australian government offered a reward of £2,000 to any person able to cross the continent through the centre and discover a suitable route for the telegraph from Adelaide to the north coast. Stuart's friends and sponsors, James & John Chambers and Finke, asked the government to put up £1,000 to equip an expedition to be led by Stuart. The South Australian government, however, ignored Stuart and instead sponsored an expedition led by, which failed miserably, failing to travel beyond the settled districts. Meanwhile, Stuart was entangled with other problems.

Some of the land he had claimed and surveyed in the Chambers Creek district on his second trip had in fact already been explored and claimed by people attracted to the area by reports of Stuart's first trip. Stuart needed to return to Chambers Creek to re-survey his claims. He left Adelaide with a small party in August 1859.

Having surveyed his own claim and several new claims on behalf of his sponsors, Stuart spent the spring and summer exploring the area west of Lake Eyre, finding several more artesian springs. Working through the severe heat of summer, Stuart experienced trouble with his eyes because of the glare, and after some time enduring half rations, all but one of his men refused to leave camp. Contemptuously, Stuart sent them home.

William Kekwick, his remaining companion, was reputed for his steadfastness and would stay with Stuart for the remainder of his career, usually organising the supply bases while Stuart scouted ahead. Kekwick went south for provisions and more men, returning with 13 horses, rations for three months, however only a single man; Benjamin Head. Fourth expedition On 2 March 1860 the three men left Chambers Creek, aiming to find the centre of Australia. As always, Stuart travelled light, taking only as much as could be carried on a few pack horses. The secret to successful exploration, in Stuart's view, was to travel fast and avoid the delays and complications that always attend a large supply train. By the time they reached (near present-day ) unexpected rain had ruined most of their stores and they continued on half-rations – something that Head, who had started the trip as a big man and weighed twice as much as Stuart, found difficult to adjust to. Water became more and more difficult to find and began to set in.

Stuart's right eye was failing. Nevertheless, they found a major watercourse in early April which Stuart named the, and followed it north-west over the South Australian border to the, which he named after Sir, Governor of South Australia, on 12 April 1860. Australia, after rain On 22 April 1860, according to Stuart's calculations, the party reached the centre of the continent. Stuart wrote: There is a high mount about two miles to the NNE which I hoped would be in the centre but on it tomorrow I will raise a cone of stones and plant the Flag there and will name it Mount Sturt after my excellent and esteemed commander of the expedition in 1844 and 45, Captain Sturt, as a mark of gratitude for the great kindness I received from him during that journey. In fact the mountain became known as after Stuart himself, not his mentor Sturt, and geographers no longer regard it as the true centre of Australia. Nevertheless, it retains its symbolic value.

The explorers were unable to progress much further north. Lack of water forced them back again and again. Stuart's scurvy was growing worse, Head was now half his original weight, and only Kekwick remained capable of heavy work. Then, on 22 May, it rained.

With water now available nearly every day, they made good mileage and by mid June were able to reach a riverbed which Stuart named Tennant's Creek (now the site of the township ). The worst of the country was now behind them and they were only about 800 km from the coast. From here, however, progress seemed impossible.

A four-day excursion to the north-west found no water at all and they had to retreat. After giving the horses a week to recover, they tried heading due north. They found another creek (later named Attack Creek) but were blocked by heavy scrub. Unlike those further south, the Warramunga Aboriginal people were hostile. On 26 June they raided the explorers' camp. One stole the shoeing rasp (which Stuart was able to recover); others threw boomerangs at the horses and set fire to the grass around the camp. Like Sturt (and unlike some of the other Australian explorers) Stuart generally got on well with the Aboriginal people he encountered but he was unable to negotiate with this group and considered it unsafe to continue.

That night, with even the indefatigable Kekwick complaining of weakness, the explorers abandoned their attempt to reach the north coast and reluctantly turned south. It was 2,400 kilometres to Adelaide, all three men had scurvy, supplies were very short, the horses were in poor condition, and the country was drying out. Nevertheless, the party pressed on at Stuart's customary rapid pace.

They reached the safety of Chambers Creek in August. A few days earlier, on 20 August 1860, the larger expedition had finally left Melbourne. Stuart reached Adelaide in October 1860. Although he had narrowly failed to cross the continent, his achievement in determining the centre was immense, ranked with Speke's discovery of the source of the Nile. Stuart had solved that which he attempted with Capt. Sturt 15 years earlier – the riddle of the nature of the centre of the great Australian continent.

He was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's Patron's Medal – becoming only the second person to receive both the and a gold watch (the other was ). Belatedly, even the South Australian government started to recognise Stuart's abilities, and was honoured with a public breakfast at. Fifth expedition James Chambers put forward a plan for Stuart and Kekwick to return north with a government-provided armed guard to see them past the difficulties at Attack Creek.

The government prevaricated and quibbled about cost, personnel, and ultimate control of the expedition, but eventually agreed to contribute ten armed men and £2,500; and put Stuart in operational command. (In contrast, the expedition had cost £9,000 to establish. That expedition had already reached the in northern New South Wales.) Stuart left Chambers Creek with a dozen men, 49 horses and rations for 30 weeks on 1 January 1861. It was high summer in South Australia and the worst possible time for travelling. Stuart was soon forced to send two men and the five weakest horses back. The heat was extreme and the party often delayed while Stuart searched for fodder and water.

They were still in northern South Australia on 11 February, the day that Burke and Wills reached the. With difficulty, Stuart's party had reached the MacDonnell Ranges when heavy rains came, allowing them to press on northwards at a much better pace.

They reached Attack Creek on 24 April 1861, this time finding no sign of the hostile tribesmen that had blocked the last attempt. At about the same time – and unknown to Stuart's party, of course – Burke, Wills and King reached their base camp at only to find it deserted. The fourth member of their party, Charles Gray, was already dead; Wills and then Burke perished within a few more days, leaving only King to be sustained by the kindness of the local Aborigines.

Stuart still planned to march north-west towards the known region of, which had been mapped by in 1858. Leaving the main expedition to rest, he led a series of small parties in that direction, but was blocked by thick scrub and a complete lack of water.

After a great deal of effort, the scouting parties managed to find another watering point 80 kilometres (50 mi) further north and Stuart moved the main body up. Over the next two weeks Stuart made three more attempts to find a practicable route over the plains to the north-west, but without success. Finally, he decided to try heading due north. He was rewarded with the discovery of 'a splendid sheet of water' 150 metres (492 ft) wide and 7 kilometres (4 mi) long which he named 'Newcastle Water, after his Grace the Duke of Newcastle, Secretary for the Colonies'.

For five more weeks the party camped at while Stuart tried to find a north-westward route to take them to Victoria River and thus the sea. The local Aboriginal people were unfriendly, lighting fires around the camp and spooking the horses, and Kekwick had to mount an armed sentry with instructions to fire warning shots whenever they came near. Provisions were running short and both men and horses were in poor condition. Finally, on 1 July 1861, exactly six months after they had left Chambers Creek, Stuart ordered a return. In the relative cool of the southern winter, they travelled fast, reaching the settled regions of South Australia in September.

When Stuart learned that Burke and Wills were missing he immediately offered to join the search for them. The first rescue teams had left some time earlier, however, and soon returned with the news that no less than 7 members of the largest and best-equipped expedition in Australia's history had died. Public exploration mania had cooled considerably. Although Stuart had now led five expeditions into the arid centre of Australia and crossed all but the last few hundred miles of the continent without losing a man, the South Australian government was initially reluctant to back a sixth effort. However, the prospect of establishing a route for an overland telegraph line became a significant factor.

The government finally provided £2,000 at the last minute on condition that Stuart took a scientist with him. James & John Chambers along with William Finke remained the principal private backers. Sixth expedition Stuart's sixth expedition was officially launched at at North Adelaide on 23 October 1861. Their first stop, before they had reached the town of Gawler, was forced by trouble with their horses. One reared, striking Stuart's with its hoof, rendering him unconscious then trampling his right hand, dislocating two joints and tearing flesh and nail from the first finger. At first it was feared amputation would be necessary, but Stuart and Waterhouse (the naturalist, appointed by the Government) were able to catch up with the rest of the party at (one of the Chambers brothers' stations) five weeks later. However they did not leave Chambers Creek until 8 January 1862.

The party comprised 10 men and 71 horses. Benjamin Head, veteran of the fourth expedition, was still too ill to accompany them. The party made good time to Newcastle Waters, reaching that point on 5 April, and experiencing conflict with the local Aborigines once again. Here they rested for a week before Stuart led a scouting party north, finding good water for the main body to move up to.

The next stage, however, proved more difficult. Five times Stuart and his scouts tried to find a route towards Victoria River without success. Finally he headed north rather than north-west and was rewarded with a series of small waterholes leading to, about 150 kilometres north of Newcastle Waters. Stuart made one last attempt to reach Victoria River before continuing north into the. On 9 June he reached a territory that had already been mapped and on 1 July the. Finally, on 24 July 1862 Stuart reached the beach at Chambers Bay (east of present-day ).

He and his Companions had crossed the continent from south to north. Members of Stuart's 1861–1862 expedition party The ten successful members of the party are listed here with their age on the day of the expedition's departure from North Adelaide.

Born Died Grave Notes John William Billiatt 19 years, 1 month 1842 1919 ( 1920) (aged 77) Devon, England Married King's sister 19 years, 10 months 1841 1915 ( 1916) (aged 74) Nailsworth, Adelaide 21 years, 4 days 1840 1877 ( 1878) (aged 37) Assistant 21 years, 5 months 1840 1912 ( 1913) (aged 72) West Tce, Adelaide John McGorrery Shoeing Smith 21 years, 9 months 1840 1914 ( 1915) (aged 74) West Tce, Adealide Died at Parkside Asylum. Heath Nash 23 years, 1 month 1838 1913 ( 1914) (aged 75) Payneham, Adelaide Francis William Thring Third Officer 24 years, 5 months 1837 1908 ( 1909) (aged 71) West Tce, Adelaide William Darton Kekwick Second in Command 38 years, 10 months 1822 1872 ( 1873) (aged 50) John McDouall Stuart Commander 46 years, 1 month 1815 1866 ( 1867) (aged 51) Kensal Green, London Naturalist 46 years, 2 months 1815 1898 ( 1899) (aged 83) Magill, South Australia.

Stuart's funerary monument at, London in 2014 By current standards Stuart was physically a small, wiry man, but in fact he was of average build of western European men at that time. He was able to endure privations and possessed a fierce determination which overrode any thought of personal comfort. He was not particularly gregarious; he had some good friends but seemed happiest away from crowds. He had a full dark beard and sometimes wore trousers and an unfashionable long-tailed blue coat with brass buttons and cabbage-tree hat. Many years of hard conditions combined with malnutrition, scurvy, trauchoma and other illnesses had rendered him practically blind, in pain and in such poor health that he spent some (900 km) of the return journey of his last expedition (1861–1862) being carried on a litter between two horses. He never recovered his health. He prepared his diaries for publication and returned to Britain, where he died two years later.

He is buried at. Places named after Stuart. Statue of Stuart in in the While Stuart was responsible for naming a large number of topographical features for friends, backers and fellow explorers, he was sparing in the use of his own name. Central Mount Stuart, which he reckoned to be the geographical centre of Australia, he had designated 'Central Mount Sturt' to honour his friend. Places named after Stuart include:.

McDouall Peak, South Australia. Stuart Street, an arterial road in the suburb of. the,., an inner suburb,.,. in the far north of South Australia,.

McDouall Stuart Avenue, Whyalla Norrie, South Australia. Stuart High School, Whyalla Stuart, South Australia. the in the Northern Territory,. an electoral division in South Australia,. the town of Stuart Range which was changed to, and. the town of, which was changed to in 1933.

John Mcdouall Stuart Quotes

A statue by honouring Stuart can be found in, while in, both a statue and a monument celebrate his achievements. In March 2010, the McDouall Stuart Lodge of Freemasons in Alice Springs commissioned a 4-metre high ferro-concrete statue of Stuart for donation to the Alice Springs Town Council to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Stuart's fourth expedition, during which he had reached the centre of the continent. The statue is located in a heritage precinct near the old hospital. In England, Stuart is commemorated by a on the house where he lived and died in, London, No. 9 Campden Hill Square. In 2011 his grave in Kensal Green cemetery, London, was refurbished to its former glory. In Dysart, Scotland there is also a blue plaque on the house where he was born.

The property John McDouall Stuart View, is available as a holiday let, restored and owned by Fife Historic Buildings Trust. References. famous Australian Freemasons. The north-west of South Australia was at that time unexplored, but is now known to be so lacking in water and soil fertility that it remains unsettled to this day. Adelaide: National Library of Australia.

11 January 1888. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

South Australia. 26 October 1860. Retrieved 4 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 27 September 1861.

Retrieved 28 November 2012. Goyder Kerr, Margaret Colonial Dynasty Rigby Limited, Adelaide 1980.

Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 16 September 1863. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

XLIX, (13308). South Australia. 9 January 1914. Retrieved 23 July 2017 – via National Library of Australia., Stuart Street, Griffith, Australian Capital Territory. Retrieved 11 May 2012. Sources.

(1949). Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Explorations in Australia edited by William Hardman. Hesperian Press. John McDouall Stuart by Mona Stuart Webster. Melbourne University Press. John McDouall Stuart Society Inc.

Whyalla Stuart High School External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to. at the. at. at. at.